Brewer Talks: “Beer With Oliver”

The Craft beer scene in India is just thirteen years old! The revolution of Craft Beers kick-started in India with Doolally – India’s first microbrewery which was launched back in 2009 in Pune. The pioneers leading this revolution were none other than Suketu Talekar, Pratekk Chturvedi and Oliver Schauf.

Oliver, who had been drawn to India 15 years ago by his passion for Beer and Travel, has been a pioneer in helping Indian Beer lovers appreciate Craft Beers. In addition to being a Brew master, he has mentored aspiring and budding Brewers to focus on Consistency, Quality and attention to detail while Brewing the most loved beverage.

Oliver, a German national with 23 years of professional brewing and distillation experience introduced craft beer to Greenland and India. He has worked with several breweries across the world and is now settled in Pune where he has co-founded Oi Brewing Company.

BRAUEREI IM FÜCHSCHEN, MEIERHOF BRAUEREI, TEERENPELI PANIMO JA TISLAAMO, BRASSERIE HISTORIQUE DU CATEAU, KARL AND FRIEDRICH and GODTHÅB BRYGHUS are amongst the many outstanding breweries he has worked with. Brewer World had an opportunity to speak to Oliver Schauf about his journey as a brewer and an entrepreneur. Below are the excerpts…

What is your first beer memory?

Malzbier. A dark, sweet, very malty beer which is just very briefly fermented to keep the alcohol below 0.5% ABV. Very traditional stuff, and popular among German kids.

Why did you want to become a brewer?

I come from Düsseldorf. Famous for its own beer style, the Altbier (a malt-forward, pretty bitter brown ale). And beer truly is ubiquitous in Düsseldorf. It has Germany’s busiest brewhouses, where Altbier is served from huge wooden casks, and the waiters insult you if you don’t drink beer. Or ask for the wrong beer (Kölsch). Düsseldorf also is home to many very old, and very traditional breweries. Where wort is still cooled in cool ships, and fermented in open tubs. That fascinated me. Especially the craft part. To make such a great product, which makes so many people including me happy, with your bare hands. Following what I then thought is a century old craft. So after school, I set out to find a job in brewing.

Can you tell us about the journey?

I was lucky and got hired as an apprentice at Brauerei im Füchschen, one of Düsseldorf’s traditional breweries. Apprenticeships are part of Germany’s formal education system: every week, it’s three days working hands-on at the brewery, and two days attending Brewing School (including beer at the lunch breaks). After hugely interesting three years I then graduated and became a Brewer and Malster, which is a government recognised profession in Germany. After my apprenticeship, I worked in a small village brewery for some time where I learnt the art of traditional lager brewing. I then joined the VLB Berlin to study Brewing Technology, a two year bachelor course, and graduated from there in 2002 as Diploma Brew master.

After graduation, I added my second passion of travelling to my career and left Germany. My first job took me to Finland, where I brewed at the Teerenpeli Brewery in Lahti for a couple of years. It was the first time I got in contact with “modern craft brewing”. Craft brewing in Germany was a very traditional business. Small breweries simply continued doing what they did for the past century or two. But in Scandinavia this traditional industry had never been there in the first place. And craft brewing was less about conservation but much more about re-invention. While American styles hadn’t reached Europe yet, brewers in Finland re-discovered the traditional Finnish Farmhouse Ale (Sahti). They were trying themselves on English, German and continental beer styles. Also ciders were popular. Often leaving the textbook behind and creating something all new. This was very exciting to see, and taught me at least as much as the traditional German brewing education. Besides beers, we were also making Scandinavia’s (maybe Europe’s?) first craft whiskey at Teerenpeli. In a small, but beautiful all-copper 15hl pot still. The smallest pot still the Scottish fabricator had ever made.

I then left Finland to join a new brewery in northern France. Setting up a used 30 hl plant in an old malt factory, including a bottling line to fill the beer and artisanal sodas into champagne bottles. It was started by an American entrepreneur, who understood how to fuse a traditional product and modern marketing. This taught me a lot about the business behind craft brewing.

From France, I then went to Russia. The Karl and Friedrich brewery in St Petersburg. Microbreweries were then booming in Russia, and St Petersburg alone counted 80 of them. Russians love beer (it is considered healthy, at least compared to Vodka), and summers there are short. From May till August, our beer garden there was sheer bursting. Guests were bribing the waiters to get tables. During the season, we were brewing 30,000 litres per month. In three shifts on an old Hungarian 5 hl brewhouse. Russia was lots of work but also lots of fun. And gave me an understanding of the real potential of brewpubs.

Who do you look up to in the industry?

Pierre Cellis, Ken Grossman and many others from the first hour of craft brewing. Those who went out, against the wind, to change the perception of beer at a time when Budweiser was considered the pinnacle of the brewing art.

You introduced craft beer in Greenland, how did that happen?

India had its hand in that. In short: I had signed up for Doolally and quit my job in Russia for that. But then my joining date got delayed again and again as files at the Excise department were moving slower than anticipated. After a few months, I really needed a job. That’s when I got a call from someone who had just set up Greenland’s first ever brewery, and was looking for a brew master. That’s how me and Alfons Fullbier, another brew master from Germany, got onto brewing Greenland’s first ever beer. We were brewing on a 20 hl Bavaria system, and mostly Danish styles, which were then sold in Nuuk’s bars. One thing working in Greenland teaches you is: planning. Everything down to the smallest screw needs to be ordered from Denmark, and then takes 1 to 2 months to come by ship. Longer in the wintertime when shipping often got disrupted by rough weather. I vastly enjoyed working there at the top edge of the world, but India was calling. So, after 12 months, I didn’t extend my contract and left Greenland for the next craft beer frontier.

What are the popular styles in Greenland?

A Danish brown ale called Classic.

You are one of the first craft brewers in India, how did this happen?

I was actually searching for it. Ever since my first visit here in 1989 I was addicted to India. I visited India regularly, every couple of years. Mostly backpacking, other times as a volunteer, and once I travelled to India overland all the way from Germany.

After my graduation from the VLB I had kept looking for an opportunity to work in India. But craft breweries came up all around the world (even in North Korea), just not in India it seemed. In 2006 then I got in touch with Suketu and Pratekk, who were planning to set up India’s first craft brewery. And opposed to other projects, they were pushing hard to get permissions from Excise. When the Maharashtra government gave them the nod in 2007, I flew to India to meet them. Doolally was a small and severely underfunded project, and they had no money to hire me. But I saw the potential (and maybe overestimated it a little), so I joined as a partner instead. And I’m still around.

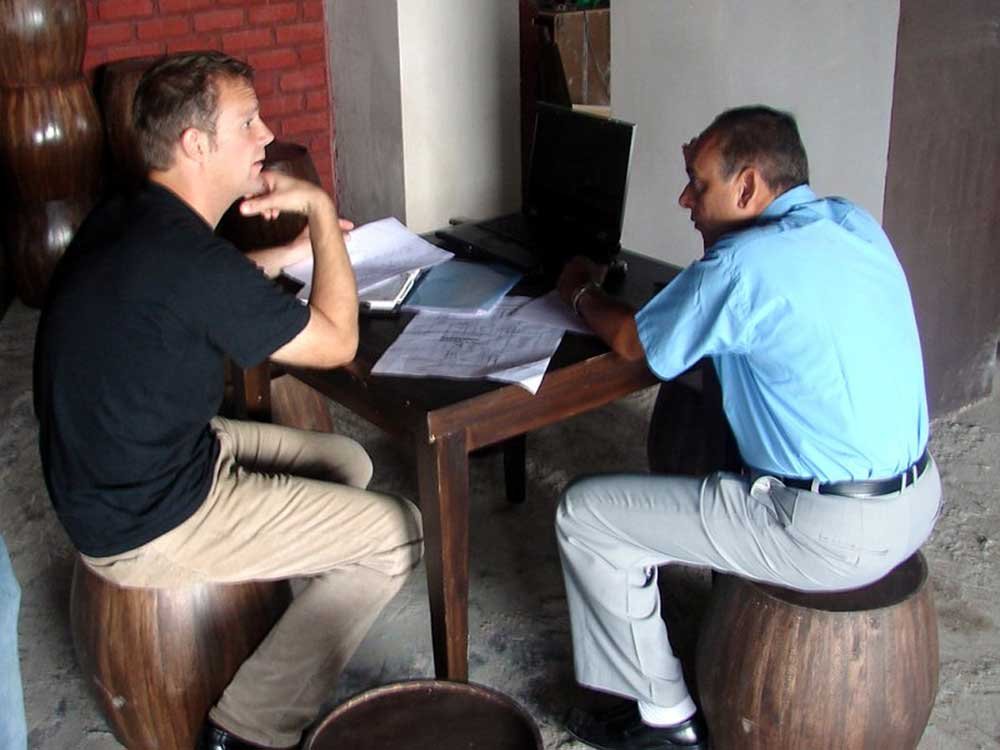

Oliver during the setting up of Doolally

How was the Indian beer industry when you started and how is it different now?

In 2008, the Indian beer industry offered us a choice between Kingfisher Mild and Kingfisher Strong. Building a microbrewery in 2008 also required a good dose of pioneering spirit. Nothing was available ready-made, and we had no funds to import anything. I taught myself AutoCAD to design tanks and brewhouses, and then had them fabricated in Delhi. We had to scavenge the Pune bazaar for valves and other fittings, and visited maltsters in Delhi to get suitable malt. When we took the first brew in 2008 (a Greenlandic ale) it certainly felt hard earned.

Also, at the same time we started, a bottled craft beer called Little Devils hit the stores. However, it was way ahead of its time and couldn’t even sell the first batch.

I am still surprised how quickly this landscape has changed. Having a good beer in India is no longer a challenge. At least in the metros. India now has an abundance of good beer brewed by great and often very enthusiastic brewers.

Opening one’s own brewery has luckily also become somewhat easier, with great Make in India equipment choices now easily available, and existing microbrewery policies in 10+ states. While for many the business might still be tough, mainly because of the remaining high taxation for beer, and a relatively small, and fragmented market, still, when seeing how much has happened in the past ten years, I am actually very optimistic about the next ten years.

Oliver at Oi Brewing Company

Tell us about your experience with Oi.

Oi is a pure brewing company, without its own restaurants. We try to focus on our beer. And utilise the new opportunities which the Maharashtra government has given us by allowing growler sales.

Oi brews India’s first organic beers. Brewed with organic raw material, and following the strict German purity law which allows only water, malt and hops as ingredients. We want to break out of the “traditional” craft beer markets, and become an alternative for all beer drinkers.

We do take the organic approach very seriously, despite the effort it often requires. For example, because organic malts are not available in India, we started growing our own organic barley and have it malted. We also invested into moving many processes in-house in order to have more control over the ingredients. For example we do have a fully equipped lab to grow our own yeast, and our popular smoked beers are made from malt we smoke in our own malt-smoker over natural wood.

Oi also offers its facilities for contract brewing, and we already have a handful of very reputed brands brewing their beer at our facility.

How important is it for a brewer to hold certifications in the beer industry?

There are two main ways to enter this industry: educate yourself on how to make great beer, or spend your own money to start your own brewery.

What are your views on culturing an “in-house” yeast strain to brew unique beers in India?

Very geeky, very niche, and not a very promising approach in my opinion. I think it would be a good start if Indian craft brewers would just start using more local ingredients instead. Craft shouldn’t be confused with gourmet food at a 5-star restaurant. It’s not “Lobster from Greenland” or “Truffles from Italy”. Instead, craft is terroir! It needs the taste of the soil if we want people to identify with it. At Doolally we have done that from day one. We use Indian malt and Indian apples. And process them on Indian brewing equipment. Whenever we have a choice, we choose local (I myself am pretty much the only “imported” part of Doolally). At Oi, we now try to take this to the next level and start growing our own organic barley. I understand that working with local malt can be a challenge at times. Simply because it is made with different priorities in mind. But the more of us are using it, the more maltsters will try hard to give us great Indian malt for great Indian craft beers.

Could you give us a brief about your consulting business (Pukka)?

I’m trying to help people who want to enter the craft liquor business to avoid making all the costly mistakes which the rest of us made (those who couldn’t afford a consultant).

If you could implement one business strategy to improve the brewing industry, what would it be?

Please contact my consulting company. ?

What is usually the inspiration for new recipes?

Things I see, smell, eat or drink. Often other brewer’s beers. Like the first (mind-blowing) IPA I tasted. A homebrew by Ben Johnson, then head brewer at the Barking Deer back in 2010. It literally blew me away. Right on the next day I ordered fancy American hops from our British hop vendor. The first Doolally IPA turned out to be very decent, but Ben had been wise to keep this a home brew. Our customers hated the “bitter beer”, and of the 1000 litre, some 800 litres had to be drunk by the Doolally brewers.

Have you travelled for beer? If yes, to where?

I have never travelled “for beer”, but also never “without beer”. The best “travel beer” I probably had was in Mauritania. It’s a dry country, both figuratively and literally. All desert and prohibition. To reach the capital Nouakchott one needs to cross a stretch of the Sahara desert without any roads. So after days in the desert one finally arrives back in civilization just to find out that there’s no beer. Luckily, the Ambassador of the Republic of Congo is a very empathetic person. He knows the meaning of thirst. That’s why he sacrificed a few hundred square feet within the (extraterritorial space of the) Embassy to run Mauritania’s only bar. Where he serves the world’s best ice cold Heineken.

Which is your favourite craft beer in India and across the world?

Free beer in good company.

Your favourite beer and food pairing?

Hamburger at 3 in the morning after usually too many good beers.

What do you do when you are not brewing?

Getting older, wiser, and better looking. Also cooking and baking. If I find time.

**This interview is a part of Brewer Talks, a continuing series of interviews with the Brewers of the beer industry and community from across the world. Brewer World will share business and personal insights from Brew-masters, Head Brewers, Brewing Managers each week to help build the industry network and consumers understand beer well.